OR

The Reports of CDL’s Death Have Been Greatly Exaggerated

by Kyle K. Courtney

*The opinions and scholarship communicated on this website are my own, expressed in my personal capacity. I am a co-author of A White Paper on Controlled Digital Lending of Library Books. I am not as the Publishers claimed in their brief submitted to the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, part of a “cadre of boosters.” I co-wrote the paper independently as part of my decades of work on libraries and access to knowledge.*

Last week, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the previous lower court’s ruling that the Internet Archive’s (IA) digital loaning program, called “Open Libraries,” was not a fair use as it violated the copyrights of several major book publishers.

But I suspect there’s something more going on in this case—the court has handed the publishers a victory using grossly imprudent language that is deeply concerning for the continuing role of libraries in society.

This decision could be used to further paint the libraries across the U.S. into a corner, replacing the library mission with that of the publisher’s mission—a for-profit mission—at the expense of the public good. And how was this accomplished? The court used the broad sword of mandatory licensing to cut out the heart of library access, preservation, collection development, and acquisition for our present and future generation of patrons.

Under some of the more extreme language in this decision it is possible that under the rationale of this case, library patrons around the U.S. will be “swapping out their library cards for credit cards” to access library collections.

And it renders library collections—on which taxpayers and state and federal governments have spent billions of dollars over the decades—devoid of any legal and fiscal value to their communities.

Quick background

In brief, IA, a nonprofit library, digitized their legally acquired physical books and made them available to loan to patrons through using their own specific flavor of controlled digital lending (CDL). Open Libraries, the name of IA’s implementation of CDL, has existed for over a decade, and its particular adaption of CDL allowed IA to lend out digital copies of books as long as it owned a corresponding physical copy, maintaining a one-to-one or “owned-to-loaned” ratio. Later, they opened the program to partner libraries, adhering to their style of CDL.

In 2020, four major publishers—Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House—sued IA, claiming copyright infringement of 127 books for which there was an existing ebook market. The publishers argued that IA’s actions unlawfully reproduced and distributed their works—which is part of the rightsholder’s exclusive bundle of rights—without permission or compensation. IA defended its actions by invoking the core of the CDL program: the fair use doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.

As a reminder, the district court had previously ruled in favor of the publishers, granting summary judgment and rejecting IA’s fair use arguments. The district court held that IA’s use was not transformative, as it merely replaced the original works with digital copies that served the same purpose as the originals. The court also found that IA’s digital copies competed with the publishers’ own licensed ebooks, directly impacting the market for these works.

Further, and most perplexing, the lower court found that, for purposes of the first fair use factor, IA was a “commercial” action because, according to the court’s reasoning, the IA website includes a link to Better World Books (an online secondhand bookstore) and a “Donate Now” button.

The key question on appeal was whether it was fair use for IA to scan and loan the digitized copies without permission, while adhering to the unique risk calculation that IA chose to follow as the legal underpinnings of the CDL model.

The Appeal

On Sept. 4, 2024 the 2nd Circuit affirmed the district court’s ruling that the Internet Archive’s (IA) digital loaning program, called “Open Libraries,” was not a fair use. Let’s look at some of the highs and lows of this recent opinion.

The Good: Not Commercial and Narrow

To the relief (I’d imagine) of every nonprofit across the United States, the court dismissed the district court’s claim that – for purposes of the first prong of the fair use test – IA’s use was commercial in nature for having a “donate” button when assessing the first factor of fair use. The publishers had argued that because IA received a small sum from a for-profit bookseller and solicited donations on its website, their activities were somehow commercial. The Second Circuit rightly noted that this argument, if accepted, would label nearly every nonprofit that asks for donations as engaging in commercial use. That’s certainly a win for the entire nonprofit library community.

Further, the court’s analysis mostly centered on the specific facts of the case: IA lending digitized books that have a previously-existing licensed ebook market. I think that this slightly narrower scope of the decision—not exactly represented well in the press coverage—leaves room for future fair use arguments regarding the digitization and lending of books without a previously existing ebook market.

This aspect of the decision, in a way, harkens back to the “core principles” of CDL from 2018 – when Dave Hansen and I co-authored “A White Paper on Controlled Digital Lending of Library Books.” The entire premise of that paper was based on a single premise: Not everything in library collections is digital – nor are many of the works going to make the jump to digital unleash libraries act.

So, despite the exaggerated rhetoric surrounding the paper and later, the case, CDL wasn;t designed library-sanctioned piracy. CDL is rooted in copyright and is designed to respect the rights of holders (we purchase the books) while expanding access to books (we loan the books). Libraries have invested billions of dollars in their collections and have acquired and maintained them for public benefit. This includes works that are long out-of-print but hold significant social and scholarly value, as well as titles for which no commercial ebook licenses are available.

As many students and patrons aptly express, “If it’s not digital, it doesn’t exist.” The critical importance of digital library access became undeniably clear during the pandemic. CDL merely seeks to uphold the library’s long-standing and essential mission to collect and lend books, now within an increasingly digital, licensed-access environment.

So, if the court was limiting this to merely books which have a viable licensed ebook market, then the decision would seem to be relatively narrow.

The Bad

However, it was not all good news. One issue was the court’s evaluation of the first fair use factor, the “purpose and character of the use.” While not entirely surprising, the court’s analysis was still frustrating. The opinion quickly concluded that the use was not transformative and thus didn’t qualify as fair use. It’s worth noting that placing excessive emphasis on the “transformativeness” element undermines the significance of the other aspects of the fair use analysis. It effectively reduces the four-factor test to a shallow, one-factor evaluation.

As a lawyer who has been involved with CDL since its inception, I assert that, while there are compelling arguments for considering CDL transformative, its fairness under the law is not solely dependent on that factor. CDL advances education, research, and scholarship, aligns with the first-sale doctrine, and serves the public interest by reinforcing the vital role of libraries. Unfortunately, the court did not fully engage with these important considerations, nor did it address precedents where non-transformative copying was upheld as fair use due to its substantial public benefits.

Another significant issue was the question of whether IA’s digital lending harms the market for original works. This could be a whole discussion on its own, but in short, the court placed the burden of proof for demonstrating that there was no market harm on IA and seemed to rely on assumptions about market damage rather than concrete evidence. The court’s economic analysis in this regard was highly flawed.

How flawed? Well, I was dumbfounded when I read the court’s decision that highlights its approach to the fourth factor: “Although they do not provide empirical data of their own,” the court said, the “Publishers assert that they (1) have suffered market harm due to lost ebook licensing fees and (2) will suffer market harm in the future if IA’s practices were to become widespread.”

This first part of this analysis is the court completely siding with an argument that publishers have been pushing for years – that library loans (which have been “widespread” since the origin of libraries loaning to patrons) are a form of market harm that should be eliminated.

The court continues that “IA argues that Publishers cannot rely on the ‘common-sense inference’ of market harm without data to back that up … We agree with Publishers’ assessment of market harm.”

This is a frustrating circle of illogical reasoning. The fourth factor of the fair use analysis requires the court to assess “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” Defendants typically do not, and often cannot, access the proprietary market data required to demonstrate that their use has not caused market harm. Of either of the parties, the publishers would certainly be better positioned to provide the court with evidence of market harm, given that they are the ones with access to their own financial statements (!)—not IA. One would think that, if the publishers had evidence of market harm, they surely would have presented such evidence to the court as it would have helped their case—rather than simply relying on assumptions.

IA did fill this evidentiary gap and presented studies from multiple experts indicating that the publishers had not suffered financial harm, but the court dismissed these studies as insufficient and contrary to “common sense.”

So, despite IA presenting data showing minimal impact on book sales, the court still ruled that “unrestricted and widespread conduct of the sort engaged in by [IA] would result in a substantially adverse impact on the potential market for [the Works in Suit] … Thus, we conclude it is ‘self-evident’ that if IA’s use were to become widespread, it would adversely affect Publishers’ markets for the Works in Suit.”

This is holding not only deviates widely from “common sense” it is wildly absurd.

What is “common sense” is something that any person could deduce easily: During the time period in question that Open Libraries was lending books to patrons, these publishers saw record breaking profits with continued use of their restrictive and costly ebook licensing schemes.

As my friend and colleague Meredith Rose recently stated on this issue, “The court here is asking defendants to prove a negative, while allowing plaintiffs to actively withhold the only information that the court will accept as dispositive. The Second Circuit has replaced the fourth factor analysis with ‘vibes.’ Franz Kafka would be proud.”

The Ugly: And Boy Is It Ugly

The market harm position of the court’s analysis was, to put it mildly, a tragedy in two parts. Digital library loaning (and maybe even print loaning?) harms the market for purposes of the fourth factor of the fair use statute.

First, some context. In a Publishers Weekly interview in 2022, the head of the AAP claimed that CDL would “irrevocably weaken the ability of authors to license their works.” Regardless of how the AAP or the 2nd Circuit now views this matter, I firmly believe that lending a scanned copy of a legally acquired print book under CDL simply does not harm the market for publishers or authors. How?

Well, to the extent that library lending has any effect on the marketplace, digital lending under CDL is functionally equivalent to lending the print version. Consider this analogy I have used since 2018: No one disputes that a library can mail a physical book it owns to a patron. CDL simply allows libraries to provide access to their physical collections through a more efficient medium—the internet. If the digital loan under CDL is controlled in the same way as a physical loan, there is no substantive difference between lending a library’s physical book and lending a digital scan of that same book.

The AAP’s suggestion that such efficiency is detrimental reflects the publishers’ longstanding preference for “friction” in digital library lending. Their, and other publishers’ solution to the friction question, is a costly and restrictive license. However, once a library legally acquires physical books, IA and its partner libraries are entitled to lend them under copyright law. Nothing in the Copyright Act mandates that lending must involve any degree of friction or a license. The law does not protect inefficiency for its own sake.

But this court has done just that – building upon the “forced ebook licensing blueprint” that was drawn up in the early 2000’s (leased/rented ebooks only, limiting to 26 check outs, and then the library must re-rent and pay again) – publishers now have a decision with language that treats every library loan as a lost consumer sale. And it rejects the idea that a library, using the same exact delivery software that is used by the publishers to deliver ebooks, could bring efficiency to the traditional library loaning system. This is certainly a dangerous precedent if left unchecked.

The 127 books in question in this lawsuit were all legally purchased and acquired. These are the same books that reside on library shelves or in off-site storage facilities, all of which were legally acquired, with authors compensated according to their publishing agreements. Indeed, this is the fundamental role of libraries: to collect, preserve, and provide access to materials that serve an important societal purpose—one recognized by the public, courts, Congress, and even publishers and authors.

Despite the exaggerated rhetoric surrounding this case, CDL is not tantamount to “library-sanctioned piracy.” CDL operates within the bounds of copyright law, balancing respect for rights holders with the goal of expanding access to library collections. This includes out-of-print works with immense scholarly and social value and books for which commercial ebook licenses are unavailable.

As many of the newest and youngest library patrons have noted, “If it’s not digital, it doesn’t exist.” The necessity of digital access became especially clear during the pandemic, underscoring the importance of CDL in preserving the library’s long-standing mission to collect and lend books in an increasingly digital world dominated by licensed access. The 2nd Circuit decision did not recognize these issues—worse, it did not address them at all.

Is a Legal Library Copy Made for Patrons Now A Derivative Work?

There was also some “ugly” and frankly, confusing, language that was also part of the market analysis by the court, but involving ebooks as derivative works. And this analysis could open a whole new can of worms for the library mission!

The court stated that in evaluating the fourth factor of the fair use analysis, it considers “not only the market harm caused by the particular actions of the alleged infringer, but also the market harm that would result from unrestricted and widespread conduct of the same sort,” quoting a case called Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, Inc, 883 F.3d 169 (2d Cir. 2018). The court relied on this earlier case law to determined that the inquiry is not “whether the second work would damage the market for the first (for example, by devaluing it through parody or criticism), but whether it usurps the market for the first by offering a competing substitute.” And here they provide a nice citation to the (in)famous Andy Warhol Foundation Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, 598 US 508 (2023) fair use case decided last year by the U.S. Supreme Court. (Both these cases are worth a read!) So, the court’s analysis includes both the market for the original work and the market for any derivative works that the rightsholder may develop.

So, by this court’s reasoning, if the publishers had the exclusive right to publish their author’s works in many different formats (and clearly including ebooks) that “the relevant harm—or lack thereof—is to Publishers’ markets for the Works in any format.”

This has been debated in library and legal circles for years. In my read, ebooks, by their very nature, do not constitute derivative works. Nor are libraries usurping the publisher’s market since they have legally acquired all these works. Again, that every library loan might be a market harm is nullified by the public policy and the law supports the very existence of libraries – non-profit, educational institutions that provide access to works that every patron can’t afford to buy themselves!

A derivative work, as defined by copyright law, involves the creation of a new and distinct work based on an existing one. Ebooks, however, represent the same underlying work, merely presented in a different format. While enhanced editions—such as interactive, illustrated, or critical editions—may indeed constitute derivative works, this is equally applicable in the realm of print. Simply displaying text on a screen via a CDL interface, as opposed to on paper, does not transform the original work into a new or derivative creation.

This distinction arises from the fact that products offered for free often provide a different user experience compared to those that are paid for. When individuals choose to pay, they typically do so for an enhanced experience. The same principle applies to books scanned for CDL versus licensed e-books. CDL books are digitized versions of physical books, lacking the sharp, crisp text and interactive features of licensed ebooks. With CDL books, users cannot highlight, change the font, look up a word with a simple touch, or utilize the many functionalities available in licensed e-books.

Moreover, the nature of library lending and control over CDL copies is a critical differentiating factor. Borrowing a book from a library offers a distinct reading environment, particularly because of the strong privacy protections associated with library loans. This contrasts with a digital reading experience where ebook vendors and publishers may scrape, process, and sell data related to the user’s reading habits. Notably, the court failed to address this argument in their analysis – and merely cast any library digitization of books as harm to the exclusive derivative right.

Libraries and Lending: A Legal Right, Not a Licensed Privilege

Libraries are not required to seek permission or obtain a license to loan books. This is a fundamental principle, yet there appears to be much confusion in the case about the libraries mission to provide access. Unlike vendors and publishers, who rely on licenses and permission as part of their business models, libraries operate under a distinct legal framework. Libraries enjoy unique copyright exemptions explicitly written into the Copyright Act by Congress, granting them the authority to fulfill their mission of providing access to materials.

This distinction was completely overlooked by the court when it suggested that digital copies should now seek licensed permission from publisher’s prior to its legally authorized uses. This stance is flat-out incorrect. The language of the court represents years of troubling narratives that have emerged suggesting that libraries should have always sought licenses to lend books, including digital ones, just as vendors and publishers do. This notion is fundamentally wrong.

Clarifying the Legal Standing of Libraries

Let me be unequivocal: libraries do not need a license to loan books, whether physical or digital. Lending legally acquired books is not illegal. Libraries are entitled to share these works, with no obligation to enter into licensing agreements or contracts beforehand. Furthermore, libraries—and their patrons—are legally permitted to make various uses of these works, including interlibrary loan, reserves, preservation, and fair use, all without needing permission from rightsholders.

This is because various exceptions in the law, including Section 108 for Libraries and Archives, a nd Section 109 known as the first sale doctrine. We know that Section 109 preserves the balance between rightsholders and libraries. When a library purchases a book, it has the right to loan that work freely, without requiring additional permissions or payments to the copyright holder. A digitized version of a legally acquired book simply replaces the physical copy, not an unpurchased one in the marketplace. Any “market harm” is already factored into the initial sale, for which both the authors and publishers have been compensated.

Congress, in crafting these copyright exceptions, explicitly enabled libraries to serve their vital function in society. Libraries provide access to materials for learning, research, and intellectual enrichment. In the 21st century, there is no reason why technology shouldn’t extend this access.

The Fiscal Burden and Licensing Restrictions

Now consider the financial implications. Libraries have spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the years—often taxpayer dollars—to build their collections. Why should they be forced to repurchase these books under a new, limited ebook licensing format? Even when licenses are offered for free, they often come with restrictive terms that limit libraries’ ability to share, loan, or use the materials as they traditionally would. These restrictions contradict the very essence of what libraries do: provide access.

Before this case, I thought the most absurd license I had encountered was the notion that teachers and librarians needed “read-along” to read books online during the pandemic. The idea that one needs permission to read a book aloud, whether online or in person, defies common sense and legal precedent. Reading aloud is a core function of education, and fair use should continue to allow these practices without the need for additional licensing. But here we are with a new case that attacks a core library principle – library loaning.

The Erosion of Ownership in the Digital Age

Licensing has eroded ownership rights for libraries, patrons, and the public. Libraries that enter into licensing agreements are not “buying” e-books—they are renting or leasing access to them under restrictive terms. These licenses often prohibit libraries from using the very copyright exceptions guaranteed by law, such as interlibrary loan or preservation. This undermines the core mission of libraries and the balance Congress intended when it created copyright law.

The Copyright Act is designed to balance the rights of creators with the public’s access to knowledge. While Section 106 grants copyright holders exclusive rights, sections 107 through 122 provide powerful exceptions, including fair use, interlibrary loan, and preservation, which allow libraries to operate freely and serve the public good.

Licenses, however, often strip away these rights, imposing restrictions that contradict the intent of copyright law. This trend must not be encouraged. If it continues, it will undermine the fundamental purpose of libraries, limit access to information, and hinder preservation efforts. At a time when technology should be increasing access, licensing is instead narrowing it, and that is a dangerous precedent. Libraries must be allowed to continue their vital work, without unnecessary legal or financial barriers.

But now a court has basically said everything a library does may need a license because the market is kIng. Any public good is irrelevant in the face of corporate profits.

The Bottom Line: To Worry or Not?

That being said, I am not launching DEFCON 1 warning. This is one bump in a long chain of attempts to curtail the library mission.

It is important to highlight that the 2nd Circuit court’s decision, I believe, still leaves considerable room for CDL to continue in various settings. The ruling specifically addressed IA’s version of CDL, Open Libraries, and found it did not qualify as fair use. IA had their own risk profile for CDL which was very different than what might be used at any other institution or library. This case is specific only to the parties, and does not impact the other existing versions of CDL.

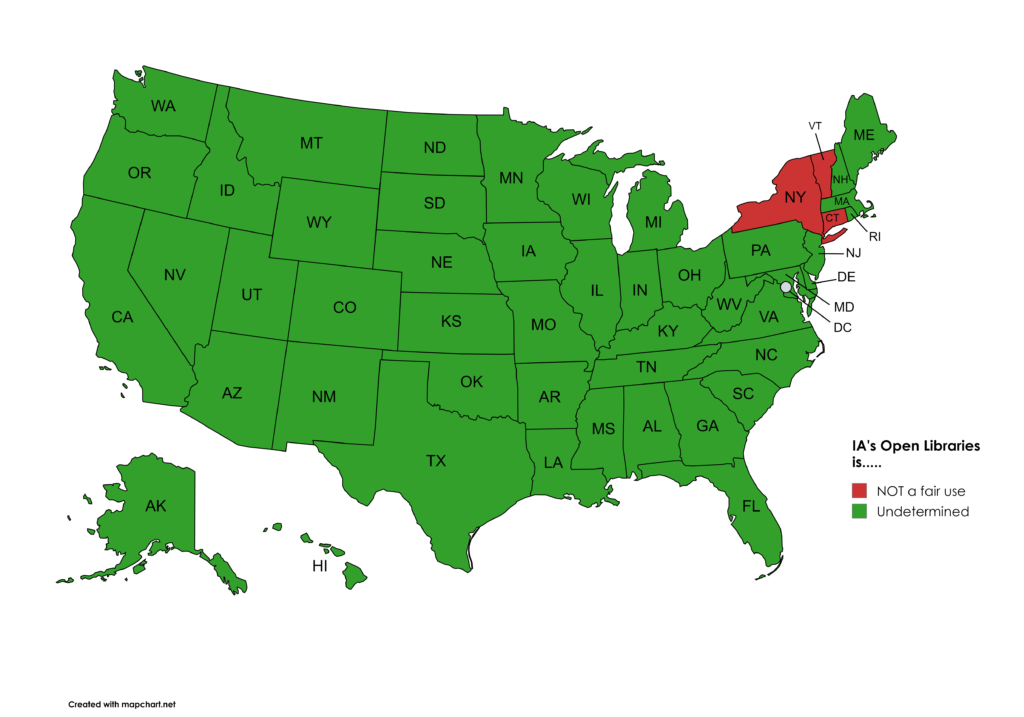

Additionally, this decision is limited to the 2nd Circuit and is not binding anywhere else—in other words, it does not apply to the 47 states outside the 2nd Circuit’s jurisdiction. In talking with colleagues in the U.S. this week and last, many are continuing their programs because they believe their digital loaning programs fall outside the scope of this ruling. Here is the map I have created to emphasize this point:

In addition, institutions around the world are using CDL, with the endorsement of large organizations like the International Federation of Library Associations, SPARC, and the Chief Officers of State Library Agencies (COSLA). This decision has absolutely no reach outside of the 2nd Circuit in the U.S., much less the world. I can say this affirmatively: other jurisdictions (with their own case law) are still figuring out the best way to use CDL for their libraries. (India, the UK, Spain, and Canada).

Moreover, the court’s opinion focuses on digital books that the court said “are commercially available for sale or license in any electronic text format.” Therefore, there remains a significant number of materials in library collections that have not made the jump to digital, nor are likely to, meaning that there is no ebook market to harm—nor is one likely to emerge for certain works, such as those that are no longer commercially viable. All these works are still potentially eligible for CDL, even in the 2nd Circuit. The White Paper’s recommended practice for CDL could greatly benefit libraries with rare, unique, local, and special collections. Again, this language semes to go back to “core CDL” from 2018 which Dave Hansen and I designed to harness our own collections that are low risk but have high value to our communities of patrons.

Pending any appeal, I also believe our response to publishers should remain consistent: This issue is not yet fully determined as it affects only a limited number of actors within a single jurisdiction. An appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court is still a possibility, and thus, this decision is not yet the “law of the land.” Nor is it global law.

TL;DR

In sum, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit’s affirmation of the ruling against the Internet Archive’s Open Libraries program raises troubling concerns for the future of libraries. While the decision is a victory for publishers, it threatens to reshape the library’s fundamental mission by aligning it with the profit-driven motives of publishers, rather than the public good.

Further, by wielding licensing as a tool to limit library access, preservation, and collection development, the ruling endangers not only the present role of libraries but also their ability to serve future generations. If this reasoning persists, library patrons may find themselves relying on credit cards rather than library cards to access collections, undermining the vast investments that taxpayers and governments have made in building library resources over the years.

However, while the recent 2nd Circuit decision is a setback for the Internet Archive’s specific version of CDL, it is not a definitive end to CDL as a whole. The ruling only applies to the IA’s Open Libraries program and is limited to the 2nd Circuit’s jurisdiction, meaning it does not affect the majority of the U.S. or the global library community. Many libraries continue to operate CDL programs, believing they fall outside the scope of this ruling.

Moreover, there remains a significant body of works, such as those not commercially available in digital formats, that may still be eligible for CDL. This case represents just one instance in an ongoing conversation about library lending in the digital age, and the possibility of appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court means the final outcome is far from settled. Therefore, CDL remains viable, particularly for materials with limited commercial availability, and its future is still evolving.

[And if courts continue to back publisher’s licensing schema, well, we’ll just change the dang license to be more reflective of the library mission! Have a look at the work we are doing in the eBook Study Group – a coalition of state legislators, librarians, and library stakeholders in numerous states working to create state laws based on consumer protection, contract law, and contract preemption to regulate library ebook contracts with publishers]