Up for a little break from COVID-19 and copyright? Well, for this post, at least a break from the COVID-19 part.

SCOTUS issued an opinion today on the “Case of Blackbeard’s Law!” (it is actually called Allen v. Cooper (18-877)). This decision is important in the copyright world, but especially for public institutions! It’s all about sovereign immunity – a risk factor we use in some copyright analysis. And it is a rare unanimous decision!

Sovereign immunity is a doctrine that protects states from federal court interference, derived in part from the Eleventh Amendment to the United States Constitution. Eleventh amendment sovereign immunity, though not absolute, states that some parties (e.g. the government) has immunity from suit in federal court. Because sovereign immunity limits the judicial power of the federal judiciary under Article III of the Constitution, absent a valid retraction of that sovereign immunity by Congress, “a State will … not be subject to suit in federal court unless it has consented to suit, either expressly or in the plan of the convention.”

However, in 1990, Congress passed the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (CRCA), 17 U.S.C.A. § 511, as part of an effort by Congress to attempt to remedy the imbalances between private and state institutions caused by sovereign immunity, but specifically for the copyright arena. The CRCA attempted to waive the states’ Eleventh Amendment immunity from liability for federal copyright law violations, through precise language that declared “any State, any instrumentality of a State, and any officer or employee of a State or instrumentality of a State acting in his or her official capacity” shall not be immune under either the Eleventh Amendment for violation of the exclusive rights of copyright holders. (17 U.S.C.A. § 511(a))

In the past, however, the caselaw in a majority of jurisdictions had found this law was not a valid exercise of Congress’ constitutional power. [Details: Congress can revoke Eleventh Amendment sovereign immunity only through a valid exercise of its power under the enforcement section of the Fourteenth Amendment if Congress: (1) makes clear that it is relying on the enforcement section of the Fourteenth Amendment as the source of its authority, and (2) ensures that any abrogation of immunity is congruent and proportional to the Fourteenth Amendment injury to be prevented or remedied.]

For a few years, case after case found that when enacting the CRCA, Congress failed to meet one or both requirements of that 2-part test. The CRCA has, therefore, had been held as unconstitutional by some district and appeals courts.

But all this came to a head when the U.S. Supreme Court took the appeal from Allen v. Cooper in the 4th Circuit, where a videographer, and his video production company, lost their suit against the state of North Carolina for copyright infringement. So, what had happened before this arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court?

The facts of this case are wild, but basically, we must travel back in time!

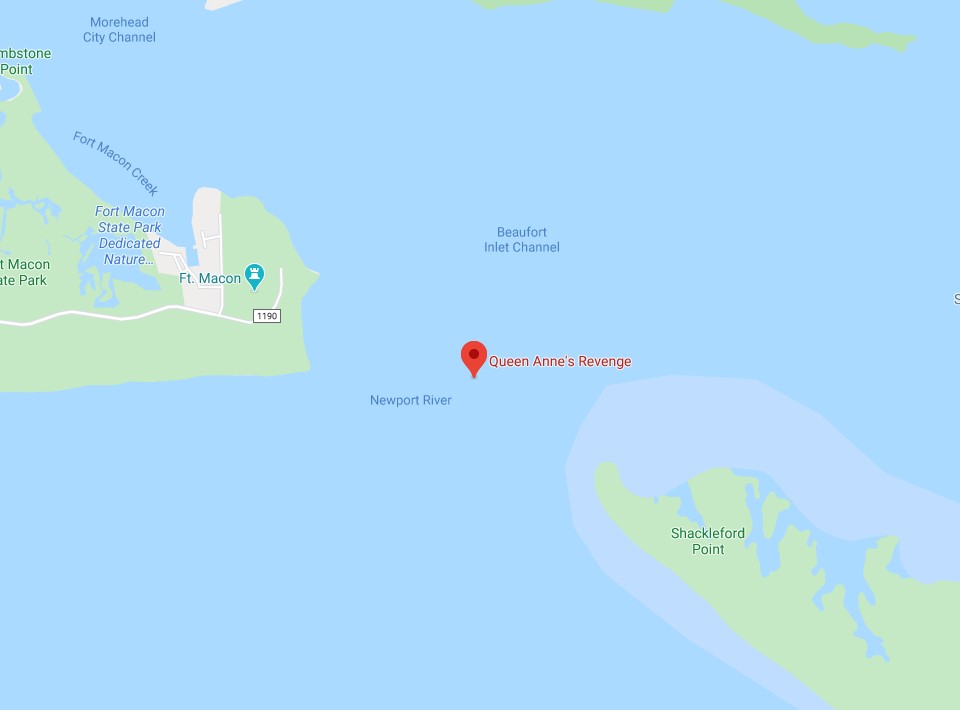

In 1718 Edward Teach, known as the notorious pirate Blackbeard, ran his flagship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, aground on a sandbar near modern-day Beaufort, North Carolina. And there it lay for hundreds of years undiscovered.

In 1996, a private salvage company located the wreck of the ship. For over a decade, Allen, a videographer, and his video production company, created many videos and photos of efforts to salvage the Revenge’s anchors, cannons, and other artifacts. Allen registered all the videos and still images of this project with the U.S. Copyright Office.

In 2013, Allen accused the State of North Carolina of infringing his copyrights by uploading his copyrighted works about the Revenge salvage project to a state website without permission. North Carolina agreed to a settlement paying Allen $15,000. (I always ask: were these uses potentially a fair use?)

However, despite that settlement, Allen later found out that the State of North Carolina had again infringed, this time posting five of his videos online and using some of his photos in a newsletter. Allen sued for copyright infringement in federal court in 2015.

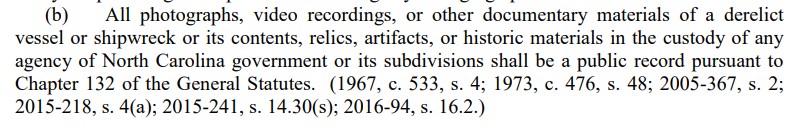

In an excellent twist, however, and in response to Allen, the North Carolina legislature created a new law called “Blackbeard’s Law” (H.B. 184, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 121- 25(b)) that explicitly converted Allen’s copyrighted works into “public record” materials not subject to copyright protection!

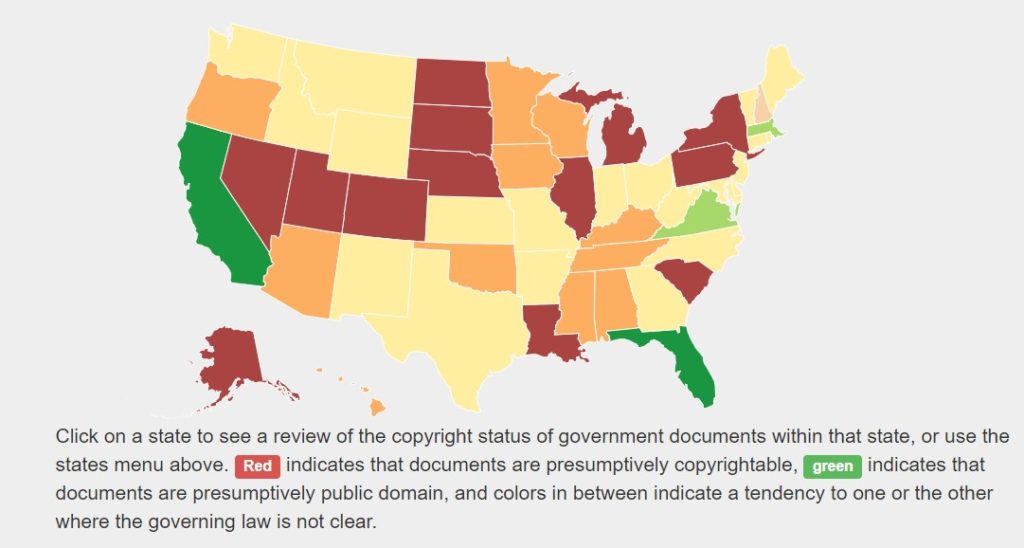

[Now that’s a law that might make even Blackboard proud! Now, in my brief opinion, this was one of the more aggressive state law reactions I have seen in response to a copyright claim. However, U.S. states do have broad legislative powers. And, when the dust settles, I always love to see more good faith actions making state materials part of the public record or in the public domain. Shameless plug: Want to see where your state stands on state copyright law? See my “State Copyright Resource Center” project!]

The narrow scope of the SCOTUS appeal, however, was all about the CRCA, not about Blackbeard’s Law, really.

The SCOTUS unanimously decided that that states are immune from copyright suits under the Eleventh Amendment. As a result, the ruling struck down the CRCA, and preserved state sovereign immunity. [For now. The Court left the door open for Congress to pass something that could withstand Constitutional muster in future. But as well all know, getting legislation through Congress might be a tall order]

Now, this does not mean that this is a free-for all! Under sovereign immunity, you can still get an injunction (and orders to stop). I do not think a state institutions will start to show the new Star Wars in the middle of a city to thousands of people or place an illegal copy online with no remedy!

However, state institutions, that are working in cutting edge copyright work – some even with low risk – should continue to consider state sovereign immunity as an important risk mitigating factor in their analysis.

In the meanwhile – Avast ye and wash yer hands!